![]()

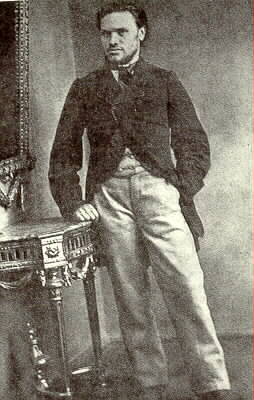

Kastus Kalinouski (1838-1864)

Kastus Kalinouski (1838-1864)

Kastus Kalinouski, publisher of the clandestine newspaper

"Peasant's Truth" and leader of the 1863-64 uprising in Belarus.

The defeat of Russia in the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the

humiliating Treaty of Paris revealed the rot of the tsarist regime and intensified demands

for reforms-above all, for the abolition of serfdom. During the first half of the

nineteenth century, because of market demands for agricultural products, landlords took

away from the peasants a sizable quantity of cultivated fields. In Belarus, the land

tilled by peasants diminished from 66 percent of the total land at the beginning of the

nineteenth century to about 50 percent in the 1850s. As a result, increasing numbers

of peasants became landless. The management of the landlords' estates was, with few

exceptions, inefficient, to the degree that landed estates employing 60 percent of serfs

were mortgaged in 1859.

Tsar Alexander II, who took over the reins of government in 1855 after

the sudden death of his father, Nicholas 1, decided to improve the internal situation by

imposing a "revolution from above" and abolishing serfdom. This he did

in:i86i. The land reform, however, turned out to be a robbery of the peasants, who

were given too little land for too high a price. The answer to the land reform was a

wave of disturbances throughout the empire-including Poland, which became

"practically a Russian province" after the 1830 uprising.

Protests in Poland against the land deprivation were coupled with a

national liberation movement and an attempt to restore the Commonwealth to its pre-1772-

borders. A revolutionary mood was also in evidence in Belarus and Lithuania. A

series of patriotic celebrations were held in Viciebsk, Vilnia, Hrodna, and other cities

commemorating historic events from the Commonwealth's past. In addition, during 1861

in Belarus alone, 379 peasant protests were recorded; of these, 125 were quelled by police

and military force.

The atmosphere was ripe for an uprising. In Belarus, preparations

for this outcome commenced in July 1862, when the first issue of the clandestine newspaper

Muzyckaja Prauda (Peasants' truth) appeared. Behind the publication stood a group of

young radicals, of whom Kastus Kalinoilski (1838-1864) was the most prominent.

Principal contributor to the publication (seven issues of which were printed), Kalinouski

became the leader of the uprising in Belarus when it broke out two months after the Polish

insurrection began in January 1863.

With his newspaper, as well as with his letters "from beneath the

gallows," written in prison, Kalinouski aimed at three categories of audience: first

and foremost, the peasants; second, the faithful adherents of the Uniate Church, which had

been officially abolished since 1839; and third, those who cherished the Belarusian

language (and were being discriminated against by tsarist authorities). The common

denominator in all of these appeals was the assertion that life in the historic

Commonwealth of Poland was immeasurably better than life under the tsars.

Reading Kalinouski's harangues today, one cannot help seeing a parallel

between the situation of the 1860s and that of the iggos in terms of political designs and

results. "Six years have passed since the peasants' freedom began to be talked

about," wrote Kalinouski in the first issue of his newspaper. "They have

talked, discussed, and written a great deal, but they have done nothing. And this

manifesto which the tsar, together with the Senate and the landlords, has written for us,

is so stupid that the devil only knows what it resembles-there is no truth in it, there is

no benefit whatsoever in it for us".

Besides oppressive taxes and corvee, a basic source of grievance

underlying the uprising was the recruitment of peasants for a twenty-five-year term of

military service. This injustice contrasted sharply with past practices in the

Commonwealth, where, as Kalinouski reminded, "whenever peasants wanted to go to war,

they were immediately declassified from their peasant status and excused from performing

corvee.

It was during the second half of the nineteenth century that the

Belarusian vernacular emerged as a mobilizing medium, and Kalinouski seized on this trend

when he complained that:

"In our country, Fellows, they teach you in the schools only to read the Muscovite language for the purpose of turning you completely into Muscovites. ... You'll never hear a word in Polish, Lithuanian, or Bielarusian as the people want."

The 1863 uprising had social, religious, and cultural dimensions.

Quite naturally, there were divisions between the right wing (the landed nobility) and the

left wing (the radical bourgeoisie and peasants). Tsarist propaganda aiming at the

peasantry, of which the government was wary, stressed the fact that the uprising was

dominated by the gentry. Indeed, about 70 percent of the insurgents belonged to that

class. However, many of them were in fact landless, and lived in towns. About

75 percent of the insurgents came from urban areas, and only 18 percent were

peasants.

The uprising lasted until the late summer of 1863. Severe battles

were fought throughout Belarus-especially in its western region, which was in closer

cooperation with Poland. But the insurgents were no match for the 120,000-strong

Russian elite troops, with whom nearly 260 encounters were fought, according to historian

A. F. Smirnov. The Russians won in the majority of cases.

The uprising of 1863 provoked harsh punishment of its participants and

sympathizers in the North-Western Province, which now constituted the General-Governorship

of Vilnia. Governor-General Muravyov well deserved the nicknames of

"hangman" and Russifier. According to tsarist official sources for Belarus

and Lithuania, 128 people were executed and more than 12,000 exiled to Siberia. The

Polish language was banned from official places. Belarus was inundated with

teachers, priests, and landlords from Russia. Poles were prohibited from acquiring

landed estates. And the bulk of money collected as penalties and contributions financed

the construction of Orthodox churches and the support of priests.

An ideological by-product of these developments was the birth of

Belarusan nationalism, of which Kastus Kalinouski is considered the founding father.

In his prison cell in Vilnia, before being hanged on March 22, 1864, Kalinouski wrote an

impassioned plea to his people:

Accept, my People, in sincerity my last words for it is as if they were written from the

world beyond for your own welfare. There is no greater happiness on this earth,

brothers, than if a man has intellect and learning. Only then will he manage to live

in counsel and in plenty and only when he has prayed properly to God, will he

deserve Heaven, for once he has enriched his intellect with learning, he will develop his

affection and sincerely love all his kinsfolk. But just as day and night do not reign

together, so also true learning does not go together with Muscovite slavery. As long

as this lies over us, we shall have nothing. There will be no truth, no riches, no

learning whatsoever. They will only drive us like cattle not to our well-being, but

to our perdition.

This is why, my People, as soon as you learn that your brothers from

near Warsaw are fighting for truth and freedom, don't you stay behind either, but,

grabbing whatever you can-a scythe or an ax-go as an entire nation to fight for your human

and national rights, for your faith, for your native country. For I say to you from

beneath the gallows, my People, that only - then will you live happily, when no Muscovite

remains over you.

Kalinouski's last letter "from beneath the gallows" has become a political credo of Belarusan nationalism.

References used in this file:

Jan Zaprudnik. Belarus At a Crossroads in History. Westview

Press.1993

Ivan Kasiak. Byelorussia. Historical outline. Byelorussian Central

Council. London. 1989

Jan Zaprudnik, Thomas E. Bird. Peasant's Truth, the Tocsin of the 1863 Uprising.

In: Zapisy Belarusian Institute of Arts and Sciences. Vol. 14. New York, 1976

This file is a part of

the Virtual Guide to Belarus - a collaborative project

of Belarusian scientists and professionals

abroad. VG brings you the most extensive compilation of the information about Belarus on

the Web.

This file is a part of

the Virtual Guide to Belarus - a collaborative project

of Belarusian scientists and professionals

abroad. VG brings you the most extensive compilation of the information about Belarus on

the Web.

Please send your comments to the authors of VG to

Belarus

History | Statehood | Culture | Law and

Politics | Cities | Nature and Geography |

©1994-04 VG to Belarus

Disclaimer